I finally understand Declarative Programming

Background

Discussions surrounding declarative and functional programming have been on the rise over the past few years. Out of curiosity, I started reading articles to understand how to reap the promised magical benefits. Just like how one doesn’t learn to swim by reading about it, I couldn’t understand the essence of declarative programming irrespective of how many YouTube videos I watched.

In computer science, declarative programming is a programming paradigm — a style of building the structure and elements of computer programs — that expresses the logic of a computation without describing its control flow. — Wikipedia

This definition abstractly made sense, but aren’t you supposed to define the control flow somewhere? Aren’t we supposed to iterate and update variables at someplace for the program to work? I was so caught in thinking of programs as blocks of explicit control flow that I simply couldn’t look outside of it.

Deciding I wanted to get knee-deep into this mysterious paradigm, I solved some problems in Advent of Code twice, once using an imperative language, and again using a declarative language. The first challenge was to choose appropriate languages for both these paradigms. Most popular languages are not of one type or the other. They are on a spectrum. (More on that in later sections)

C++ is my choice for imperative because it is the least declarative programming language I’ve used (No offense). I chose Haskell as the declarative language because I’ve wanted to learn the language for years. Technically, it’s a functional programming language, which is a type of declarative. By the way, “Learn you a Haskell for Great Good” is an amazing source to learn Haskell.

As I finish this journey, I’ve documented my learnings in this article. I hope this becomes the article I wish I had found when I started.

Disclaimer

To emphasize the difference between these paradigms, I’ve only used rudimentary C++ in most examples. No STL, etc. The examples do not compare Haskell and C++ code, instead imperative and declarative programs. It is possible to write STL based succinct C++ code, but it doesn’t help understand the essence of imperative.

Lessons

The program approaches the human language solution

Consider the following task,

Given a list of numbers, remove all numbers which are 0 and sort the remaining.

For example, given [5, 0, 8, 0, 0, 2] the program should return [2, 5, 8]. Following is the solution in C++,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

vector<int> filterAndSort(vector<int> arr) {

vector<int> result;

int n = arr.size();

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (arr[i] != 0) result.push_back(arr[i]);

}

// Bubble Sort

int m = result.size();

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) {

for (int j = i+1; j < m; j++) {

if (result[i] > result[j]) swap(result[i], result[j]);

}

}

return result;

}

Create an empty vector called result. Iterate over every index (i) from 0 to n of the input array and check if the array element at index is not 0. If the element is non-zero, push the element to the end of result vector. Assign the size of the filtered vector to variable m. Iterate over each element in index (i) of result vector and over each index (j) starting from i+1 to end of array. If element at index i is greater than element at index j, swap the two elements in the result array. Return the final sorted result vector.

That’s a LOT of words for a problem whose solution can be explained to my rubber duck in one line. This is the solution in Haskell,

1

filterAndSort = sort . filter (/= 0)

Even with no prior knowledge of Haskell syntax, one can see that the function does two things — filter and sort. This function reads as “filter a list by retaining all elements not equal to zero (/= 0) and sort the remaining list”. The task statement requires me to do two things, and the Haskell function does exactly two things.

This is the crux of Declarative Programming. The program should roughly be the human language explanation of the solution. It expresses what it does, instead of how to do it. Stuff like iteration and updating variables is implementation detail that should be hidden.

Modern C++ has functions that can help abstract away some of the clutter. However, there will still be implementation detail that does not belong to the problem statement.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

vector<int> filterAndSort(vector<int> arr) {

vector<int> result;

for (auto item : arr) {

if (item != 0) {

result.push_back(item);

}

}

sort(result.begin(), result.end());

return result;

}

Building upon the earlier definition, one might say that declarative programming is simply about having a ton of utility functions. That’s only a part of it. Having a good number of utility functions definitely helps abstract away implementation detail. However, it goes even deeper. Let’s try to solve the following problem,

Given two characters, return true if the first one is an opening bracket and the second one is the matching closing bracket. Return false, otherwise.

Following is the solution in C++,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

bool areMatching(char a, char b) {

if (a == '(' && b == ')') return true;

if (a == '[' && b == ']') return true;

if (a == '{' && b == '}') return true;

if (a == '<' && b == '>') return true;

return false;

}

For a C++/Java programmer, this looks perfectly sensible and readable. Now, let’s see the Haskell solution,

1

2

3

4

5

areMatching '(' ')' = True

areMatching '[' ']' = True

areMatching '{' '}' = True

areMatching '<' '>' = True

areMatching _ _ = False

areMatching is a function that takes two parameters. By virtue of pattern matching, we can create multiple definitions of the same function for different values of parameters. The final function definition is the fallback when none of the earlier ones match. This is the closest you can get to the problem statement.

Declarative programming is a race to make programs comprehensible even to non-programmers. Every other jargon you hear surrounding declarative programming are only means to achieve this goal.

Ability to express logic effortlessly

To write programs declaratively, a language should allow users to compose and reuse elements fluently. The fundamental building block of Haskell is a function. It is simple to compose different functions into one — which makes for programs that require very little overhead beyond the problem domain.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-- Returns the product of the largest three numbers in an unsorted list

productLarge3 = product . (take 3) . reverse . sort

-- Returns all pairs of coordinates (0,0), (0,1) .. (0,n-1), (1,1) ... (n-1,n-1) given n

-- Similar to mathematical set comprehension.

getAllCoordinates n = [(x,y) | x <- [0..(n-1)], y <- [0..(n-1)]]

-- Example function invocations

productLarge3 [8, 3, 2, 5, 1]

getAllCoordinates 5

Note: Haskell functions do not require parameters if they simply reuse other functions, like productLarge3 above. The syntax is beyond the scope of this post.

If you are unable to understand the syntax above, fret not. They are the same functions as the following in C++,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

int productLarge3(vector<int> arr) {

sort(arr.begin(), arr.end());

reverse(arr.begin(), arr.end());

auto largest3Elements = vector<int>(arr.begin(), arr.begin() + 3);

int product = 1;

for (auto it : largest3Elements) {

product *= it;

}

return product;

}

vector<pair<int, int>> getAllCoordinates(int n) {

vector<pair<int, int>> coordinates;

for (int x = 0; x < n; x++) {

for (int y = 0; y < n; y++) {

coordinates.push_back({x, y});

}

}

return coordinates;

}

One of things that immediately strike me is how easy it is to compose functions together in Haskell. In Haskell’s productLarge3 the operation of sorting and reversing an array is as simple as reverse . sort. In C++, there is the extra overhead of .begin() and .end() calls. Each statement in the imperative method corresponds to a single word in Declarative. We can go the extra mile and define a helper function for every action done in C++,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

vector<int> sortArray(vector<int> arr) {

sort(arr.begin(), arr.end());

return arr;

}

vector<int> reverseArray(vector<int> arr) {

reverse(arr.begin(), arr.end());

return arr;

}

vector<int> take(int n, vector<int> arr) {

return vector<int>(arr.begin(), arr.begin() + n);

}

int product(vector<int> arr) {

int product = 1;

for (auto it : arr) {

product *= it;

}

return product;

}

int productLarge3(vector<int> arr) {

return product(take(3, reverseArray(sortArray(arr))));

}

In this case, the C++ definition ends up being close to Haskell’s definition with a little more overhead. The burden of defining these methods lies with the programmer though.

Take the other example of getAllCoordinates . Haskell allows you to use set builder notation to generate the result. In imperative, the only way to do this is by using loops. Note that even Haskell has to internally represent the function as loops. It is just syntactic sugar that helps programs look closer to the problem domain. This point might seem petty for many folks, but the benefits really add up over larger codebases.

Powerful standard libraries

Emphasizing the point again, some languages make writing declarative programs easier. One important requirement for this is to have a great set of standard library utilities that make it easier to work with the problem domain. Haskell has a gigantic set of standard libraries, which have its own search engine to find the function you want. Having a great standard library alone does not solve the problem, take Java for instance. It has an amazing standard library but does not allow you to compose logic elements as easily as Haskell does. Streams API is the right step towards declarative, but it is still declarative code in a largely imperative world.

Define the problem domain

A language needs to only solve effortlessly in its intended problem domain. Haskell is a general programming language, so it works great on primitive data types, arrays, maps, and other standard data structures. If we try to solve for a different domain using Haskell, say compilers (with data types like symbol tables, abstract syntax trees, etc), we have to define the required functions and classes (or the loose Haskell equivalent of ADTs) to make the code expressive.

The most popular functional programming language in the world is Excel.

— Someone at Microsoft.

Unbeknownst to most, SQL and Excel are declarative programming languages. Think about it, the following SQL statement

1

select name from employee where hire_date > '2021/01/01'

is similar to this Java statement,

1

2

3

4

5

// Does not compile, only for representative purposes

employees.stream()

.filter(employee -> employee.getHireDate().isAfter("2021/01/01"))

.map(item -> item.getName())

.collect(Collectors.toList())

The advantage of SQL is that it is specialized to the domain of querying over tables. It is not very useful or maintainable to perform anything outside its domain of tables (e.g., handling JSON data). SQL queries express logic in syntax matching the human language solution, which for this example is “Get all names of employees who were hired after 1st Jan, 2021.”

A Pleasant Consequence — Pure Functions!

A function is pure if,

- It always returns the same output for a given set of input parameters. This is possible when the function’s result depends only on its input parameters and constants.

- It has no side effects i.e., the function does not modify the input parameters, or any variables outside of itself.

When sticking to the definition of Declarative Programming, this is pretty obvious. We never intend to compute different values for the same input at different points of time when defining a solution. Unless explicitly specified in the problem, we never expect the solution to modify the state of anything outside of the function itself. Some deviations are when the problem requires us to update a file or read dynamically from a file.

All real world solutions are mostly pure, and programs should ideally reflect this if they intend to be declarative. This also improves the reliability of programs, you can always be sure the function will return the same result for identical inputs.

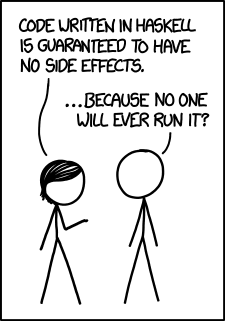

Obligatory xkcd: https://xkcd.com/1312/

Obligatory xkcd: https://xkcd.com/1312/

Note: One perceived distinction is random numbers. Programs that depend on random numbers are expected to return different values on every run. However, computers cannot generate truly random numbers, only pseudo-random numbers. These random number generators also take inputs such as system time. As long as even these inputs are constant (which is infinitely improbable), the output will be the same.

Conclusion

“Representation is the essence of programming.” — Fred Brooks

Declarative Programming is writing code along the lines of the human language definition of the solution. It has more to do with how we write programs than which language we are using. It is possible to write imperative code in declarative languages and vice-versa. Although some languages make it much easier to write programs declaratively, you can always strive to write declarative programs in every language.

This post is not trying to say that writing imperative code is wrong. Imperative programming shines when you need full control for performance-reliant programs. For the rest of the population, expressing your programs declaratively is something to consider.

✨ Follow me on Twitter to read more of my tech explorations :)